LGBTQ+ People Are Not Going Back

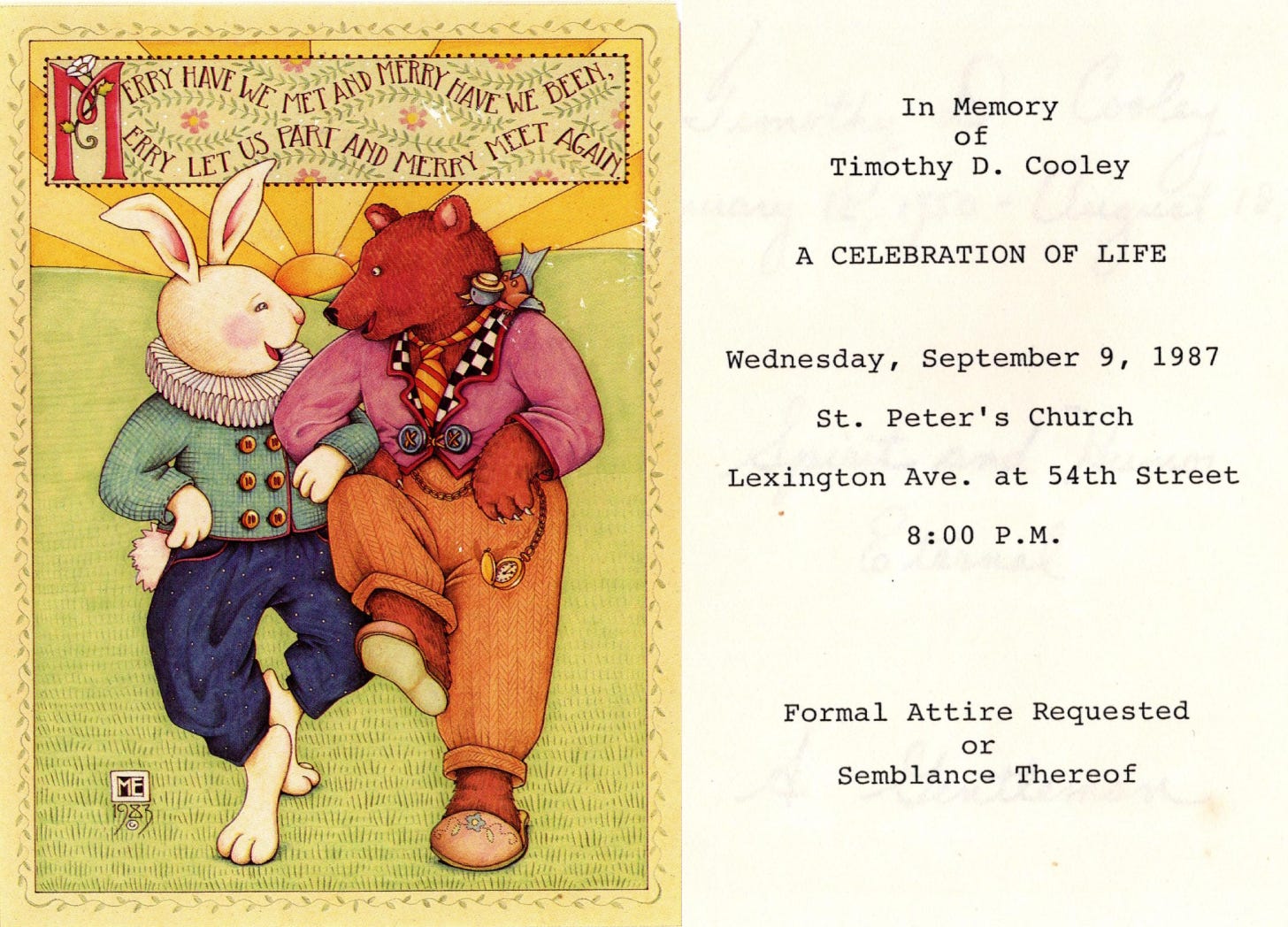

Merry Have We Met and Merry Have We Been • Merry Let Us Part and Merry Meet Again

A Note:

I’m publishing this essay today instead of my usual Wednesday time in support of a planned action by Julia Serano. Trans rights, and by extension, LGBTQ+ rights are in the sights of the incoming administration. We’re seeing it already. I will not be silent.

Read about the action here. I invite you to add your voice on Substack and out in the social media universe. Let your representatives in Congress and in local politics know that LGBTQ+ People Are Not Going Back.

The sound of my phone ringing tears me from sleep, and I roll over, look at my clock and register the time. It’s 3:14. 3:14 in the morning. As I jump out of bed to answer it, I’ve got a pretty good idea who’s calling. The only person who ever calls me at this late or early hour, depending on one’s perspective. I scramble out of bed and make my way the 3 feet to where the phone sits on my dresser. Everything is close at hand in my tiny studio. My snug, spare little home measures 13’x13’ with a long hallway and great closet space. 169 square feet that belong to me. Industrial gray carpeting, a mirrored wall––to make the space seem larger––design accents of black and red for the chic of it, and very, very few possessions. I like it that way. My first apartment. My name on the lease. It’s rent-controlled and cheap. I pay $259 a month to live in one of the most desirable neighborhoods in Manhattan. It’s 1985, I’m 24 years old, single, out and proud, and so happy to be living on my own.

Standing in the dark, I see the lights from the street slip through the blinds like fingers searching for something hidden. I pick up the phone and say hello.

Yes, it’s Tim.

“I need you. Can you come over and help me?” I can hear his frustration; he’s cursing quietly under his breath. He sounds absolutely beaten down, exhausted.

“Sure, sweetie. Give me ten minutes. I’ll be right over.”

I throw some clothes on, not worried about what I look like, I’m only going across the street and the chance of running into anyone I know or hope to impress is slim. The only people out at this hour are the gay boys and drag queens making their way home from the bars.

Tim lives across the street at the corner of 16th and 7th Avenue in New York City. Chelsea. The neighborhood is very gay, very fun, very colorful, and often pulses with undertones of sorrow and fear. Sorrow because those of us who live here see the progression of the disease. The disease that turns beautiful, robust young men into skeletal shadows of their former selves, their once-glowing skin marked with KS lesions, their vitality stripped away leaving the specter of an almost certain death sentence, hovering above them like a storm cloud following them wherever they go. They often wear heavy makeup to attempt to cover up the dark red bruises that loudly declare the diagnosis to anyone vaguely in the know. They do it to keep themselves safe from harm, a valiant attempt to be anonymous, even though scarlet letters mark their skin. No makeup can fully hide this cancer. Chelsea is a melting pot riddled with HIV and AIDS. It’s the 1980s and death and loss are ever present, a thrum beneath the disco music that celebrates and mourns our lives.

The night doorman at Tim’s building, Joey, nods to me, sleepy at his post. I’m a regular here at all hours, no announcements of my arrival are necessary. I get upstairs and let myself in––the door’s unlocked. He never locks it anymore; he leaves it open for his caregivers so we can come and go. He doesn’t consider his safety the way he used to. There’s a part of him resigned to this, his fate. He knows nothing can hurt him more than this, nothing that really matters, he can taunt death, because in the end he wins by losing. He knows he’s dying; it’s just a matter of when. A member of the Hemlock Society, Tim needs to feel he has some agency over when he leaves this life. It’s crucial that he feel in control of something, when everything seems out of his control. He’s 35 years old. 35.

At least several times a week, Tim calls me in the middle of the night to help him change his bed linens and his pajamas. His night sweats are prodigious. I strip the bed, remake it, bundling his laundry for pick up, he can’t do it anymore, and won’t let me. I flip the mattress so the sweat spot––like a crime scene outline of his body––is on the bottom. I towel him off and help him get into dry pajamas, and then I tuck him in. He’s weak and can’t handle certain self-care chores anymore. His stubbornness has waned a bit; he lets me help but grumbles bitterly to save face. He’s lost his independence; that hurts most of all.

In the morning, I go back once he’s awake, and lift the mattress up, leaning it against the wall of his studio apartment, so it can air dry during the day. He moves to his couch to rest, or if he’s got medical appointments, I help him dress. I can’t be there all the time, he doesn’t want that, and I have a job, but I help as much as I can.

There’s a few of us who tend to him. All women––that’s no surprise–– we do show up. Even his doctor is a woman. Most of the gay men he knows are not as available, I think they see their mortality reflected in their dying friend’s suffering; the mirror terrifies. I understand, though it also makes me angry. He needs those men.

His primary caregivers are me, Anna––a gorgeous Southern diva I’m crazy for––she’s straight, so it’s just a lovely fantasy; and Barbara, another beauty––a lesbian I lust for. She has no interest in me, but loves to flirt, confusing me no end. I’m naïve and hopeful. Anna and Barbara are flight attendants, so I’m first on call; I’m always home and live so close by.

Tim was originally my dad’s friend first, not mine. That’s how we met. He’s part of a group of 4 or 5 men. Four if my dad is single, five if dad has a beau. The core group is my dad, Tim, Stan, and Steve. My dad loves Tim, but keeps some distance with regard to the messiness that comes with severe illness. He just can’t handle it. He donates to all the AIDS organizations, which is needed, too.

In times of health, they play together, vacation together, go to theater and the opera, and on New Year’s Eve, they dress in elegant tuxedos, finished with sparkling cufflinks, cummerbunds; my dad favors an antique pocket watch and fob, it finishes his look. They dine in style every year at One If by Land, Two If by Sea on Barrow Street in the Village. And there are costume balls at The Monster in Cherry Grove, on Fire Island. Tim takes center stage doing brilliant drag, and always goes home with a first-place trophy.

The costume balls deserve the space of a story all their own, and one day, I’ll tell it.

When I met Tim, I didn’t like him at all. He was rude, sarcastic, dismissive, and angry. He lacked the filters of diplomacy that most of us possess. Whatever was on his mind came out of his mouth, with seemingly no regard for anyone’s feelings. His diagnosis made it worse.

I was afraid of him.

When he was diagnosed, I can’t say that he went through any kind of spiritual transformation that made me want to be his friend or help with his care. I think I changed. I was living in the middle of an ever-present crisis and my generous nature coupled with my codependence––my need to “save” people––kicked. in. Of course, I couldn’t save Tim, but I could be of use. It wasn’t always good for me, it was stressful and scary, and I didn’t realize at the time that it took a major toll on me.

I saw his fear, his sadness, his anger, and the isolation. I related to the isolation. He was already challenged by life before he became ill. His sharp tongue kept people at arm’s length. He was a pro at alienating himself. Now it was even harder. I saw him being cheated out of a life he’d only started to live. He enjoyed a multitude of talents; he was a make-up artist and a gifted caterer. He had no clue how to let love in.

At first, I started doing simple errands for him. Picking up food if I was going to the store, making trips to the pharmacy for his meds. Then I got more involved, on call, especially in the middle of the night. It’s when he needed me the most.

I bonded with his family. They were Republican mid-westerners with strong Christian values. They loved their Tim and stood by him. No fire and brimstone speeches. No talk of sin. No excommunication from the family. Just love. They’d visit as time and money allowed, but if there was a crisis, they’d be there right away. Their hearts wide open, they showed no fear. His mother Rose was an angel.

Occasionally, Tim would be hospitalized, on the AIDS/HIV floor, 7 Spellman, at St. Vincent’s Hospital right down 7th Avenue, just a few minutes away. These were the early days when orderlies would bring food to the doorway, laying the trays on the floor in the hall. They’d kick the edge of the tray to scoot it into a patient’s room, frightened to get too close.

He called me one day and asked me to stop by his place. “Bring a notebook, I need to make some plans.” He wasn’t going to let some well-meaning, but incompetent friend take care of planning his memorial. This was Tim’s farewell; he was a party planner with a vision. A vision that involved gorgeous male waiters in tuxedos circulating freely among the guests, offering endless hors d'oeuvres and pouring bottomless glasses of champagne, the DJ spinning classical music, Diana Ross, Grace Jones, and Donna Summer, with some Yma Sumac thrown in, just for fun. The most fabulous drag queens he knew would hand each guest a long-stemmed rose and a chocolate-dipped strawberry as they entered the sanctuary for his farewell. He chose the location, purchased the invites, leaving instructions for us to send to his guest list when it was time.

Tim wrote his eulogy; it was witty, sophisticated, and of course, contained a slight edge of sarcasm––he’d mellowed some, but old habits are hard to break––and he asked his best friend, Stan, to read it at the service. That was the plan.

He lived for two more years––and died at 37––before the drugs that might’ve saved him became available. He died in hospice at St. Vincent’s with his mother at his side.

We gathered in style––formal attire requested––to celebrate his life. When Stan walked up to the pulpit, he paused, slowly scanned the crowd, took a deep breath and burst into tears. In addition to being Tim’s best friend, Stan was a doctor whose practice was solely devoted to caring for people with AIDS and HIV. He fought a losing battle every single day, and it was killing him in its own insidious way. To be a doctor , a gay man as well, and watch your patients die one after another, helpless to save them, was soul-crushing for him. He died not long after from liver failure brought on by alcohol abuse. The epidemic took him, too, in its own way.

Anna, our graceful Southern belle, stood up and read the eulogy while grasping Stan’s hand, they held each other up as she read Tim’s words.

Tim’s vision was an evening filled with love and care. With joy and gratitude. He wrote us a love letter, begging us to cherish life, to love, to dance, to shine, and never, ever hide.

The service ended with the DJ spinning Bette Midler singing Friends.

We hugged each other, we wept, and then we danced.

Afterword: Tim was buried in the family plot back home. His gravestone only notes his birth.

If you’re getting value from my writing and you believe writers should be paid for their work, then I want you to know that this is the only place you get ME

And for all of December, I’m having a sale! 50% off for annual subscription. That’s $25 for year of The Next Write Thing. I think you should go for it!

Or donate if you’re not into subscriptions but would like to support my work.

Thank you!

Text of my crosspost - all true. ❤️

"LGBTQ+ People Are Not Going Back is an important initiative by Julia Serano of Switch Hitter to foster solidarity and action in the fight to maintain LGBTQIA+ rights already won, now threatened. Click through Nan's post to read more about the action.

Merry Have We Met and Merry Have We Been • Merry Let Us Part and Merry Meet Again is the important story of Nan's caregiving to her friend, Tim Cooley, who died of AIDS in 1987. Her narrative speaks to the role that many women played during that devastating time, when national leaders, friends, and family alike turned their backs on generations of gay men.

Qstack is proud to support both Nan and Julia's efforts with this crosspost. Please hit that ❤️ button to show your solidarity with them, and Restack if you can."

Thank you, Nan, this story, that you write so well, is so important. I was in Manhattan at the same time - the 80’s- it’s really hard to believe, now, what it was like. Friends suddenly just gone.