The Spy Who Loves Me

She didn’t seem interested in me. I found her hard to read. She was kind of confusing, maybe a little bit sketchy. She was odd, for sure.

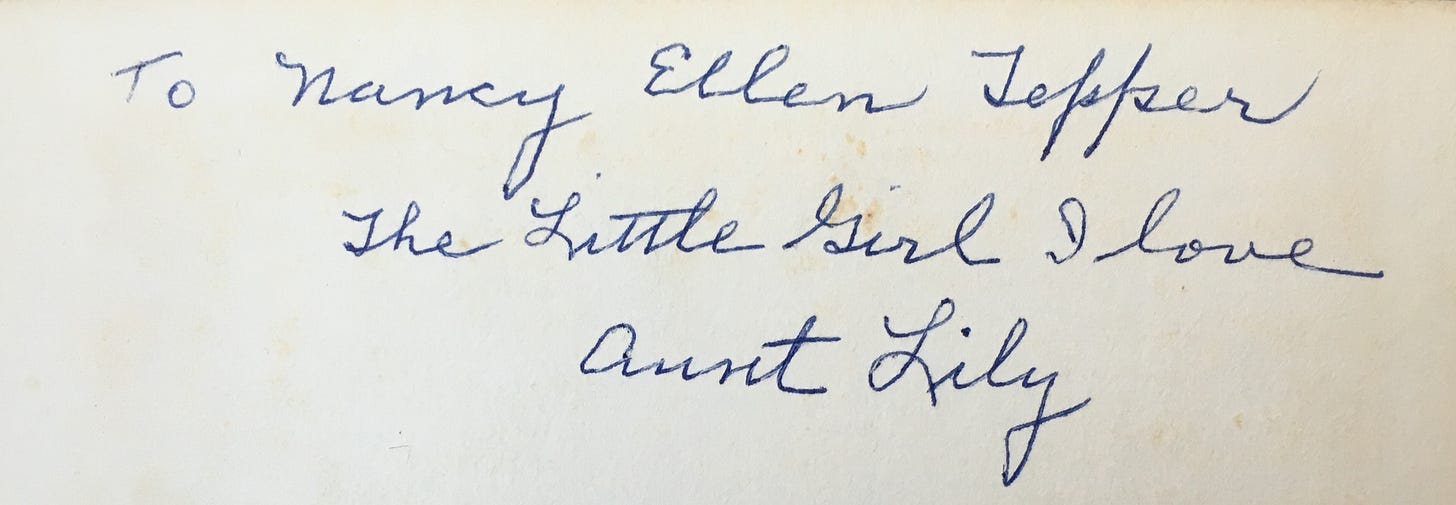

I was in first grade when my great Aunt Lily introduced me to Harriet. Lily visited us one day in 1967 and brought Harriet with her. Apparently, she’d met her in the neighborhood, and thought we’d be a good match. My family lived in New York City on East 81st Street, and Harriet lived on East 87th Street. We both played in Carl Schurz Park. Other than that, I didn’t think we had much in common, and she was a few years older, a big girl. But Harriet seemed cool. She dressed like a boy, in dungarees, high top sneakers, and a dark blue hoodie, and she wore these big, black, heavy eyeglasses. I was so jealous. I loved boy’s clothing, and the only place I was allowed to wear a hoodie was at the beach in the summertime. I also wanted eyeglasses. Desperately.

And Harriet didn’t seem interested in me. I found her hard to read. She was kind of confusing, maybe a little bit sketchy. She was odd, for sure. It wasn’t the fit my aunt had envisioned, but it was nice of her to try.

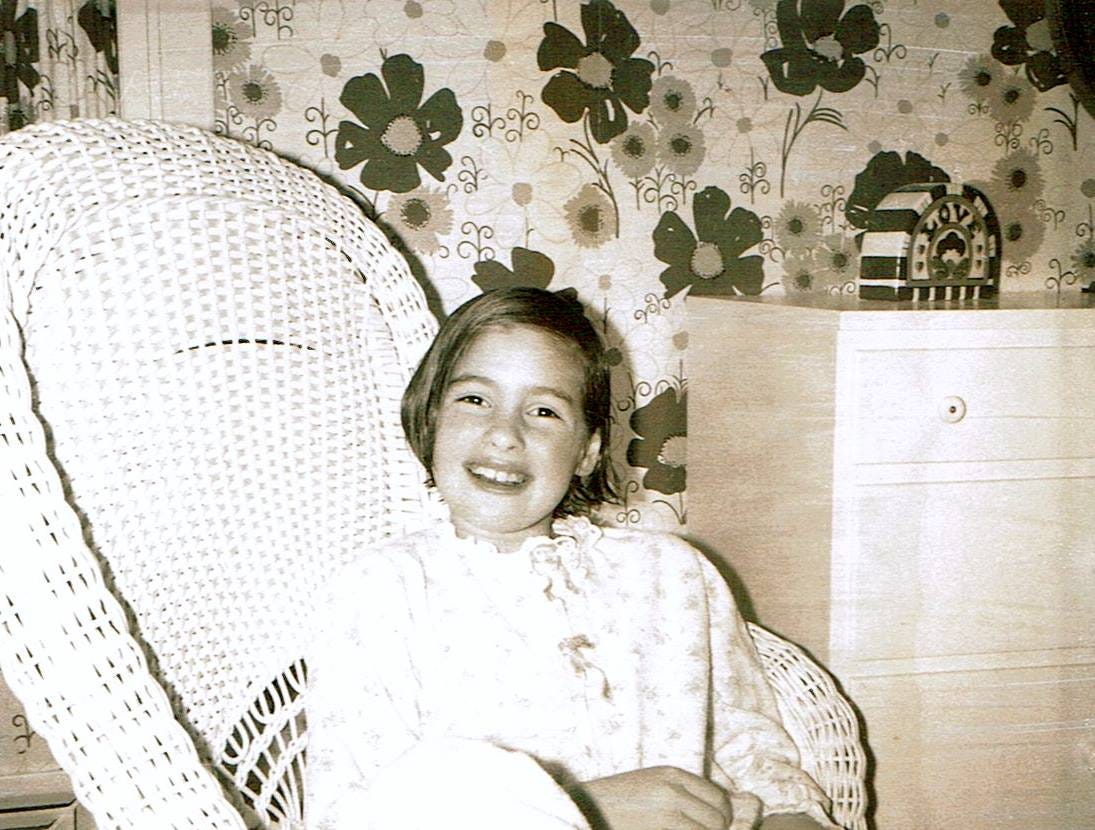

After I finished 1st grade we moved to the suburbs at the beginning of summer. My parents wanted to make sure there was time for me to settle in and get to know some kids before 2nd grade started. I was excited about living in a house, instead of an apartment. The best part was having my own room. I didn’t have to share with my little brother anymore! My mom let me pick out the wallpaper, and I chose a mod red, white, and blue flower design. It was happy wallpaper. I had lots of shelves for all of my books. I loved to read more than anything. There was a window seat where I could sit and read, and daydream. From my quiet spot I’d watch the activity on the street from the window.

There were lots of kids in the neighborhood, and we all just went outside to play by ourselves. It was 1968 after all. We didn’t need grown-ups to watch us, like we did at the park in the city. The neighborhood kids were okay, but they weren’t very welcoming. Being a new kid was tough.

In September, I went to my new school. When I walked into the classroom, my new teacher approached me, a big smile on her face. She wasn’t anything like my 1st grade teacher in the city, Miss Seidman. Miss Seidman was young and beautiful, and had the most whispery, soothing voice. I think I was probably in love with her. This new teacher was Mrs. Bloomrosen. She had short dark curly hair, a rough, scratchy voice, wore very red lipstick, and she smelled like cigarettes. Mrs. Bloomrosen welcomed me warmly, and called me Nan. No one had ever called me Nan before. To everyone else I was Nancy or worse, Nancy Ellen. I loved my new name. It didn’t seem as girly. Mrs. Bloomrosen really saw me. I was probably in love with her too, but in a different way.

By the time I was in 3rd grade, I had slowly started to make friends. I was beginning to feel like everything was going to be okay. One morning in February I got up and got ready for school. When I said good bye to my mom she looked at me, raised her eyebrow, a concerned expression on her face, and said, “You don’t look right. Do you feel okay?” I told her I felt fine. She said, “I think you should stay home.” But I wanted to go to school. We were having a spelling test and I didn’t want to miss it. I knew how to spell every word on that list, and I loved getting A’s. So I got on the bus and went to school.

The next thing I remembered was waking up in the nurse’s office in a white metal bed, blankets drawn up to my chin. My pants were wet, like I’d had an accident. Sunlight was pouring through the windows making the most horrible headache I’d ever had feel even worse. I couldn’t move my head without excruciating pain. Later I found out that I’d had a seizure in front of the whole class. That had never happened to me before. My parents took me to several doctors, where I was x-rayed, hooked up to machines, tested, finally given a diagnosis of epilepsy and sent home with some medication.

I didn’t understand any of it, and no one really explained it to me. There was a stigma about having epilepsy and my parents tried to protect me. They didn’t even call it epilepsy. I had a “convulsive disorder.” And no one ever told me what my classmates had all witnessed, which must have been very frightening for a bunch of 8-year-old kids. After that they were scared of me, and started being mean. Then a month later, I had another seizure in my classroom. Again. In front of the kids. Again. I woke up in the nurse’s office. Again. But this time, I knew what had happened.

It felt like something broke inside of me. Just when I had started to fit in, I was out. I began to spend a lot more time by myself. It didn’t feel like it was by choice. Isolating myself felt like my best defense against the cruelty of the kids. I cried often and hard. I found comfort in books, hours spent in the safety of my bedroom. I would curl up in my window seat during the day, and read. At night, after lights out, I’d crawl under my desk where the nightlight was plugged in and I would sprawl on my belly, elbows bent, my chin propped in my hands, a book spread open on the floor in front of me.

One day, looking for a new book to read I saw something I’d forgotten all about. Up there on the highest shelf of my bookcase was Harriet! Harriet the Spy by Louise Fitzhugh, the book my Aunt Lily introduced me to when I was 6. It had been a big girls’ book and I was a big girl now. I opened it up and dove in.

It took me back to the Upper East Side, NYC, and good memories of Carl Schurz Park. Back to that kid, who I had thought was so cool, dressing like a boy, with her dark blue hoodie and glasses. Harriet wasn’t like any girl I’d ever met. She was odd. I loved how odd she was because she was like me. But unlike me, Harriet wasn’t polite. She didn’t seem to be afraid of much either, like I was. She was ornery, brave, funny, independent, and very, very smart. She was––as my Aunt Lily would say––a wise ass. Harriet said whatever was on her mind. I got to know her, a page at a time, learning about her life, and her friends. I wanted to be just like her. I wanted to be tough and smart, and brave. Maybe even a little bit ornery.

Harriet’s favorite sandwich, tomato on white bread, became my favorite sandwich. She ate one every day. I switched between tomato sandwiches and my other favorite, sardines. On sardine sandwich day, I was guaranteed to sit alone in the lunchroom. The other kids hated the smell of sardines and I was getting good at keeping people away.

Harriet’s goal in life was to become a famous writer. She wrote in her green composition book, in all capital letters, and had a spy route where she would chronicle her observations about the people she spied on. Her opinions were often harsh. She did things like hide in a dumbwaiter to watch one subject, or peering through a skylight to watch another. Then she would write about all the people in her world, and she was very honest. A little too honest at times. She was fearless while I was afraid of so many things. I wasn’t comfortable stirring the pot so I let Harriet do that for me. She wasn’t a cookie cutter kid. She was unique. I wanted to be unique, too. Maybe that would make me feel better about my outcast status.

I got myself a notebook and started to write about the people in my world. I wrote in all capital letters, just like Harriet. (I still do!) I wore dungarees, and hoodies, and eventually I even got glasses. Mine were legit, unlike Harriet’s. The glasses she wore were her father’s old ones, the lenses missing. They were a good disguise. She even wore them to school now and then because she thought they made her look smart.

Harriet had been pretty popular until something terrible happened to her, and then she was suddenly alone. Her friends had discovered her notebook with all of her blunt observations about them. They felt betrayed and Harriet started to be ostracized by them. She missed her friends, and to be welcomed back into the fold, she needed to learn how to be humble and tell small lies every now and then. To do that she had to get out of her own way, give up some of her stubbornness. The details of our stories were different, but I understood her pain. I loved Harriet.

It's taken me much longer to understand humility. I’m doing work in my life now to heal old wounds, to forgive the people who hurt me, and try to understand more fully the circumstances of my life. But instead of lying, even just a little, I’ve had to tell the truth…a lot. 12 Step recovery is helping me do it. To be brave.

I’ve read Harriet the Spy every year for 55 years now. Because of Harriet, I wanted to become a writer. I wanted to be just like her. She had called herself a writer when she was 11 years old. I’m finally claiming it. I’m braving it at 62. Harriet has been my beloved friend and hero for all these years.

I still have the book my Aunt Lily gave me. The dust jacket is gone, the pages discolored, but Aunt Lily’s inscription is very much intact. I still love Harriet M. Welsch and I know she loves me.

You made me want to read Harriet the Spy again and truthfully, I think I will. There’s something about re-reading your favorite childhood book that resonates with me (along with much else written here), my childhood re-read is A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, it’s so dog eared and yellowed and loved. I keep thinking I should buy a new one but I won’t, even with the cover hanging off and rubber banded together it’s the most nostalgic thing I own.

So beautiful. So much packed into this piece! Thank you for bringing Harriet back, and for your bravery. I wish I had known your Aunt Lily better. I'm glad you had her love. (And I had forgotten your middle name!) I've been thinking about our shared experience of juvenille epilepsy, though I never had seizures at school, my heart goes out to that scared, confused little girl. I love you so much. (P.S. You have always been a writer. A wonderful writer. Now you are a public writer--a gift to all who read you.)