His Last Night

I needed a ritual of some sort to come to peace with his pending departure.

He finally admitted himself to hospice, seven days before he died. Well, actually, he didn’t. I did. For months I begged him to consider it, but he refused, wordlessly, his lower lip jutting out as he shook his head, unable and unwilling to speak his refusal. He said no because he was still looking for a cure and because he was terrified of dying.

My father was the king of magical thinking. And it would have to be magic, because there was no hope. He’d exhausted all possibilities having refused the initial one at his diagnosis––the one that might have saved his life––the one he refused to act on, because his vanity overpowered his will to live. He needed a total laryngectomy, but he dug his heels in. The possibly life-saving operation would require a tracheotomy. He didn’t want to have a “hole in his neck.” He ended up with one anyway, when it was too late, because his airway was blocked by the tumors he thought he could conquer by chasing solutions that were never going to work. So, in the end, he was able to breathe, he couldn’t speak, he had a hole in his neck, and he was dying.

It was a Friday afternoon at the end of June in 2011. The appointment was meant to be informational. To answer his questions, and hopefully calm his fears, but earlier that day, Dad shut down, he stopped communicating. He closed his sad brown eyes and never opened them again. He lay on a hospital bed in the living room of his small one-bedroom apartment. He’d lived there for more than 30 years. It was clear that it was going to be up to me to sign him in to hospice.

The doorbell rang, a thud on the first beat, a jarring clang on the second. That thing had been broken for over 20 years. But he didn’t care about things like that even though he wouldn’t need to fix it himself. He just needed to let his super know. Those are the thoughts that ran through my head as I went to greet the hospice nurse who’d arrived for our first appointment.

I opened the door, and was surprised to see a slim, middle-aged white man standing in the hallway. I expected a woman. Sexist tropes run deep, even for me, a committed feminist. He introduced himself; his name was John. He had a gentle vibe I appreciated and needed. My heart was pounding, my stress level was through the roof. My desire for relief and release was unquenchable. I was tired, I was sad, I was going to lose him, I was going to miss him. A part of me just wanted it to be over.

I hoped the nurse could engage my father in the conversation, even though he was non-responsive. I wanted him to make the choice, to sign the consents. But it would fall on me as his healthcare proxy to sign for him.

John assured me that he was past being able to do it for himself. It occurred to me that Dad might have shut down because he couldn’t choose. He was so scared of death. John was right. I did have to do it for him.

The papers were signed, and an action plan was put in place. John taught me how to administer Dad’s morphine. I did it willingly, wanting to ease whatever pain he was in. I think I also was aware that the drug would hasten his death. I wondered if I was killing him. The use of morphine in hospice is a type of sanctioned euthanasia, in my mind. I believe in that. And no, I wasn’t killing him. I was just easing his way. It was time for him to go.

Each day went by, sitting with him in the apartment, waiting and not knowing what would happen when. We ate and talked and watched TV, as he lay in his bed a few feet away. His aide was there, and Robert, dad’s boyfriend, would come over after work, and we’d cram into the little space. My brother arrived the day of his 46th birthday, and he and I waited together, taking time away in the evening to go out and toast his birthday––and our father––at a local bar. Some birthday.

On Wednesday evening, the 29th, I was sitting at his bedside, talking to him, telling him stories. His caregiver was in the next room, on the phone with her children. As I sat quietly, I reflected on the memories I shared with him, and I began to think about his refusal to be buried. Of his refusing the rites that come with the death of a Jewish man or woman.

When I was actively participating in my Jewish community, one of the ways I did service was by volunteering for the Chevra Kadisha, our holy society. It was the responsibility of the members to practice the ritual of Tahara, the preparation and purification of the body for burial. The practice was segregated by sex. Women performed it for deceased women, and men for men. We cleansed and dressed the body in the traditional white burial shroud, we recited prayers as we worked, and someone sat with the deceased until the funeral.

I was deeply committed to this ritual, and my father was having none of it. He chose cremation, which is not a practice performed by Jews, historically, though it’s certainly more common these days. That’s what he wanted. That’s what he got. Added to that, he forbade us to sit shiva (to grieve in fellowship with loved ones for a week), he wanted no memorial service, no recognition of the life he’d lived. He wanted to disappear.

I needed a ritual of some sort to come to peace with his pending departure. To say goodbye in a loving and gentle way. On that Wednesday night, I gathered the softest washcloth and towels I could find in his linen closet. I made up a bowl of warm water scented with just a drop of his favorite fragrance, Lagerfeld. That fragrance was my father.

I stood by his bed, and began to bathe him, preserving his modesty, never lifting the sheet that covered him, draping him carefully, moving from his right foot, up the length of his body and down the other side, talking softly to him the whole time, sharing my favorite memories, hoping that he could hear me and take in my words of love and acknowledgement. He was unresponsive. He didn’t resist at all. I kept looking at his face, for some recognition, some sign of awareness, but there seemed to be nothing left.

When I reached his hands, his beautiful hands, his elegant, expressive, soft and very strong hands, I examined his palms and lifelines as I washed them. Our lifelines were almost identical. I remembered the times we’d sat and compared them. I used to wonder when his lifeline would end. And I wondered about mine. Now, it seemed I had my answer, at least as far as his was concerned. Now. Soon.

I cleaned each finger and trimmed each nail. I saved the clippings in a plastic Ziplock for later, as they needed to go with him to the crematorium. The whole of him, not missing anything.

I took hold of his right hand, and squeezing it, I looked again for a nod, a flutter of consciousness, I told him I loved him, and he squeezed back so lightly that I wasn’t sure it really happened. But then he did it again, a gentle pulse of pressure, reaching out beyond his inability to utter words anymore. Letting me know he was still there, cognizant of my presence.

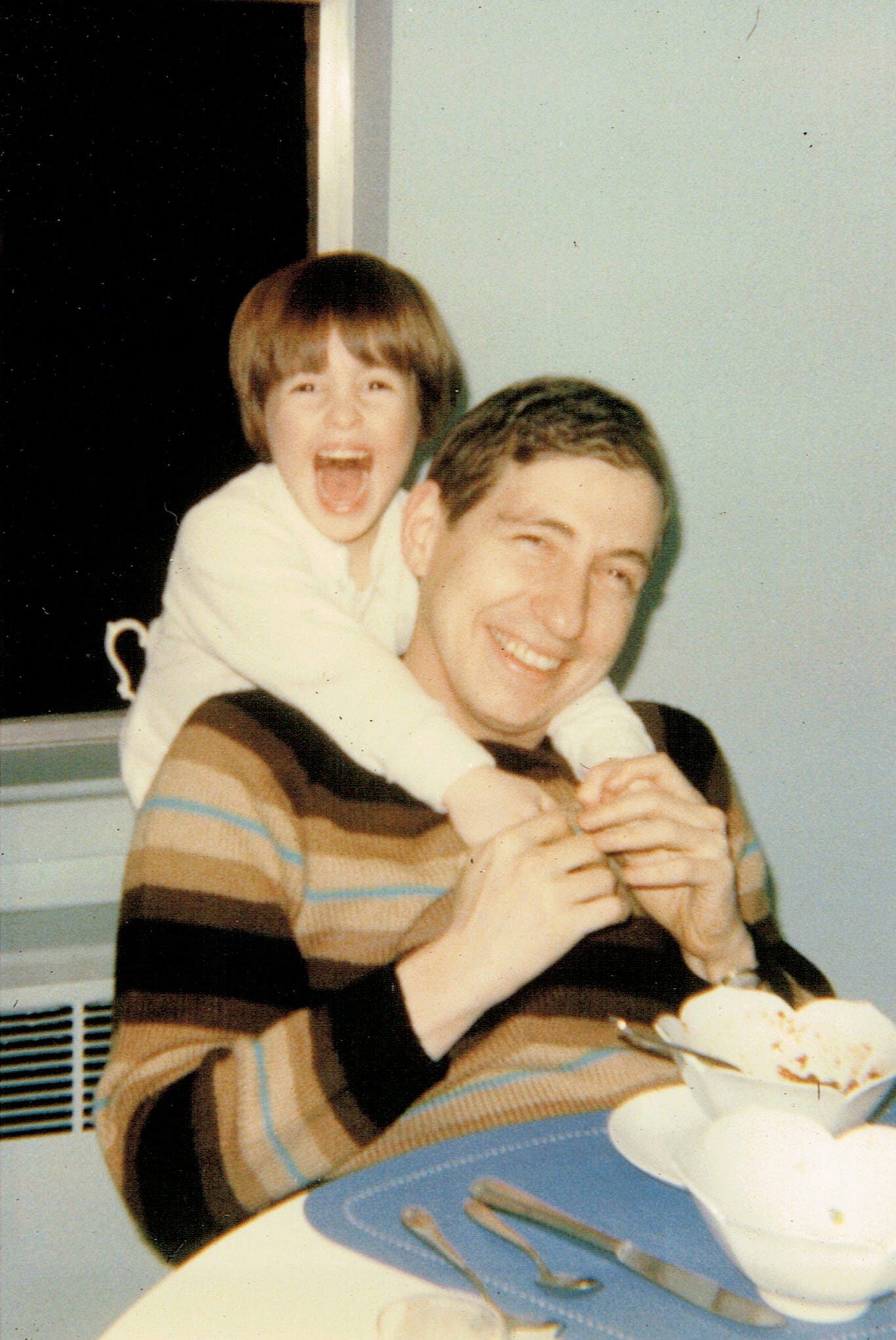

I changed the order of the ritual, because I wanted to end at his head. Normally we start at the head and work down, right side then left. I gently cleaned his face, wiping blood away from his mouth. I combed his scant hair, gathering the loose hairs from the comb and adding them to the baggie. I kissed his forehead. “A kiss on the keppie” (the word for head in Yiddish). He used to say that to me when I was a little girl.

When I was finished, I put the washcloth in the bag as well. His skin cells must go with him, too.

I resumed my place, sitting at his side. I held his hand. And as I talked to him in a quiet voice, I told him I loved him again, and he gently squeezed my hand a final time. I went back to my mother’s place to sleep and returned in the morning. He died during the moments I stepped away from his bed to get the morphine for his next dose.

As I was going through his possessions after he died, I took the bottle of Lagerfeld home with me, so that when I was missing him, I could open it, inhale, and bring him back to me, ever so briefly.

If this post was meaningful for you, please restack, comment, and like. It helps me grow and reach more readers! xo

Please support my writing and become a paid subscriber!

If you’re not into paid subscriptions but want to support me from time to time you can do that by clicking the button…

AND….I’ll be teaching a 5 Week Zoom Master Class in May all about the ins and outs of publishing on Substack: So, You Want to Write on Substack But You Don’t Know Where to Start? Find out more or register now!

Nan,

This moved me. The tenderness, the ritual, the knowing that even in silence, there was recognition. That last squeeze of his hand—there’s so much in that.

The way you honored him, even when his choices clashed with your own beliefs, speaks to love in its most complex, unvarnished form. Not neat, not easy, but deeply present.

Thank you for sharing this.

Jay

What a lovely way to bring us through the heartbreak into peace.