It’s Shocking. Just Shocking.

They put an oxygen mask over my mouth and nose and ask me to count backwards from 100 by sevens. I never make it past 86.

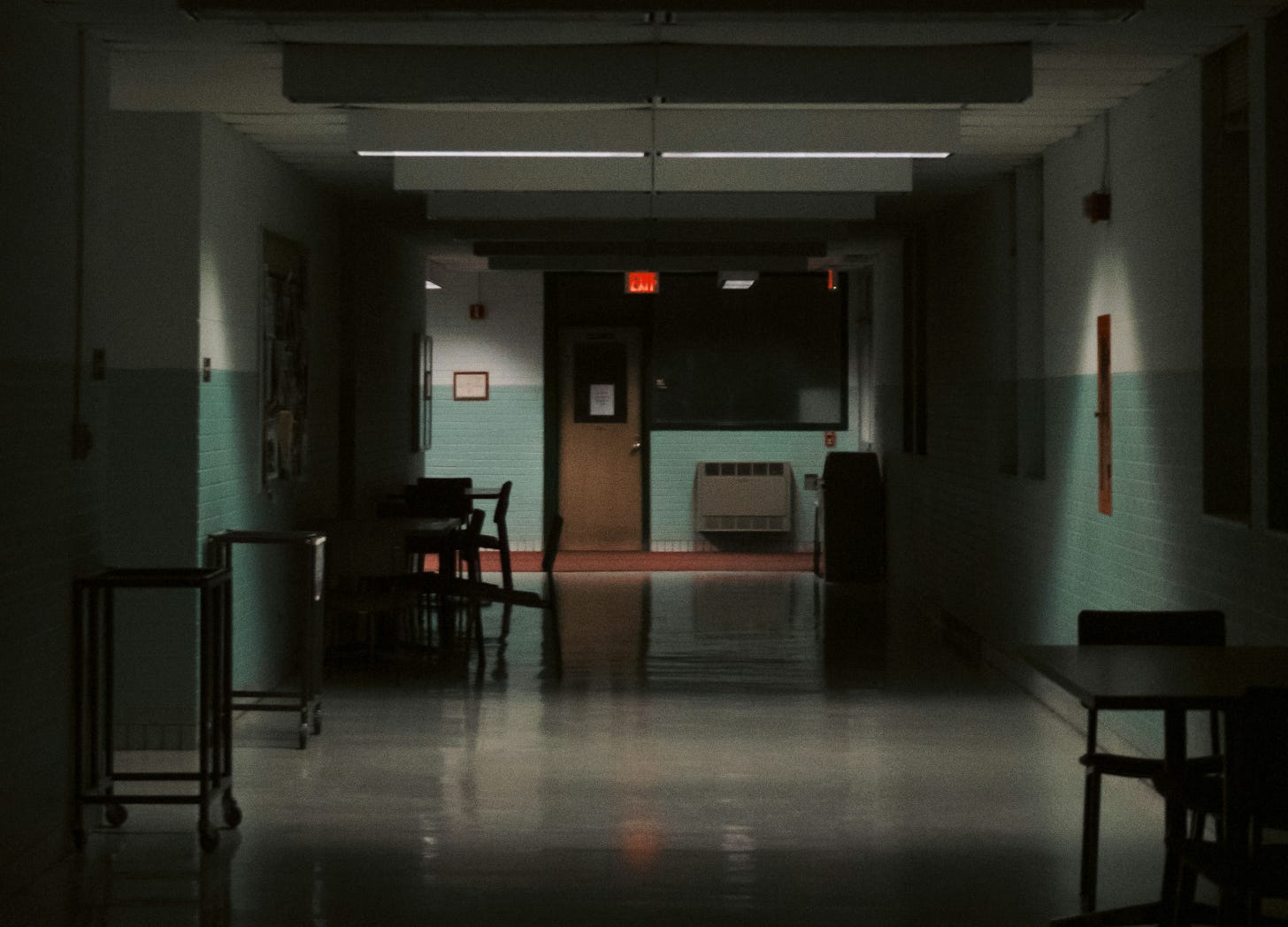

The fluorescent ceiling lights buzz on and blind me at the same moment I hear his voice in the doorway.

The same words, at the same time, three mornings a week. Every week.

“Morning, Ms. Tepper, I’m here to do your IV.” His voice never fails to rouse me from my heavily drugged sleep. I hate these mornings. I love them, too. I know what’s coming, and there’s something in me that looks forward to it, even though and because of.

My roommate moans and grumbles, turning away from the light. I look over at her as she wraps herself tightly in one of the thin cotton blankets that barely keep us warm.

What is this one’s name? Amy, Charisse, Debbie? She got here after midnight, sent up from the emergency room. This one was in the ER for four days, waiting for a bed. I never know who or what I’ll get. Some of them scare me, they’re so unhinged. They come and go. I’m here the longest of anyone on the unit. It never occurs to me that I might be scary, too.

I miss the lush weight of my blanket at home, the softness of my red and black buffalo plaid flannel sheets, the embrace of my overstuffed down pillows cradling my head. So much more friendly than the pancake they dare to call a pillow, here.

The tech’s name tag reads “Clarence Diggs.” It comes into view as he sits down next to me on the edge of the narrow bed. The cover that protects the mattress crackles as I move over to make room for him. I’m appalled that the hospital cares more about the longevity of mattresses than it cares for our comfort. The vinyl makes me sweat.

He sets his blue plastic bin of supplies down between us on the bed and pulls out what he needs to start the line. Alcohol swab, needle, and catheter. Paper tape to hold it all in place. He wraps my forearm with a tourniquet, and reaches for the back of my right hand, holds it firmly, and slaps it hard four times to bring a vein to the surface. He swipes the spot with the swab. His hands are like ice; his touch rough and hurried. He needs to do a lot of these, and fast. He inserts the needle into a vein. It always hurts. Clarence just doesn’t have the touch. I’ll be bruised again. I’ve had him before, but he’s just one of many who can’t get it right.

At least today, he gets it in one stick, not several. More often than not, Sal, the nurse in the treatment room, has to redo the IV. I wish they’d just let me skip this part and let Sal do it later. They could think of it as a generous form of harm reduction. One less insult to my body and my dignity.

I try to go back to sleep but I feel anxious. These are the mornings I don’t have to get up for 6:30 vitals; it would be nice to sleep in. The next interruption is a loud, stern voice over the P.A., issuing a rote greeting––“Good morning, 9 West, it’s 6:30am on Wednesday, June 9th, 2010, please report to the day room for vitals.” The entire unit drags itself out of bed, shuffling down the hall in slippers and pjs. We form a queue for blood pressure readings, body weight, temperature, and O2 sats. Then, breakfast.

Being spared from the morning meal is one of the few good things that happens today. I’m not allowed to eat until afterwards, because of the anesthesia. I’m not missing a thing. I rarely eat breakfast out in the world, but we’re expected to eat here. The nurses watch and keep track. The food sucks: each meal a miserable confrontation with overcooked scrambled eggs that are poured from a container, there’s lumpy gray oatmeal, and orange juice that never tastes right, a hint of metal at the edges of each sip. I won’t even mention the coffee. It’ll be more than two months before I can taste a great dark roast again. And everything is served with brittle plastic utensils. No knives!

I’ll eat a Snicker’s bar later, pulled from my secret stash. I’m able to buy them now that they’ve given me the “privilege” of a half-hour chaperoned group walk outside, twice a week, with a quick stop in the lobby gift shop to stock up on snacks. I don’t care about the walk that much. I want the chocolate.

I try to sleep until it’s my turn, though the P.A. system is still in full swing, and people walk back and forth speaking loudly. The pay phone rings constantly, just down the hall. It’s how people reach us, and we reach them. No cell phones permitted. We’re not allowed to close our doors. When it’s time, Barbara, my favorite nurse, comes to my room to fetch me for the procedure. She’s much better at a gentle wake up greeting than Clarence or Mr. P.A.

Most of the nurses here wear green or blue scrubs. Some of the women wear scrubs with teddy bear motifs or circus clowns. Not Barbara. Barbara owns a wardrobe of brightly colored, Hawaiian muumuus, that reach just shy of the floor. I can see her sneakers below her hem. The combination doesn’t work but it doesn’t matter, because it’s Barbara. Those muumuus are the only uniform I ever see her wear. I have a feeling she wears them all the time. She’s short and fat; round really, with dark curly hair, a melancholy smile, and the most loving nature. I trust her. She once confided in me that she also deals with depression, has even been a patient in a treatment room just like the one I’m about to enter. Every time she comes for me, I get out of bed, I’ve already changed into the scrubs they give me to wear for the procedure, and I slide my feet into my lime green Crocs. They’re at least one size too big for me.

She looks down at my Crocs and lovingly chides me, “One of these days, you’re gonna break your neck in those things.” I know she’s right, but I love the attention of this reliable repartee we engage in every time, right before the main event. I never tell her about all the times I’ve tripped and fallen already.

We walk through the dining room together, to the heavy steel door that separates the unit from the treatment room. She pulls out an enormous ring of keys from a secret pocket deep within the folds of her muumuu, the keys jangling as she searches for the one that will unlock the door. Those few moments, waiting, are a hard reminder that I’m on a locked ward. No way in, no way out, without that special key.

There’s a little waiting room for outpatients who come for treatment. I’ll be there one of these days, but for now, I get express service. Barbara points me in the direction of my gurney for the day, and I lie down. This is where I get my vitals taken. And Sal’s the man who does it. I find his smile and his warm hello soothing. And like clockwork, he does a new IV, and rolling his eyes, he shows me he understands my frustration with the “double dip.” Sal IS a natural, no pain, no bruising, ever.

I lie on my gurney, waiting while patients are wheeled out of the treatment room, and quickly replaced by the next person in line. I listen to people in various states of consciousness, coming back from the anesthesia, the sounds of coughing, and throat clearing, remnants of the effects of the drugs rattling in their lungs.

When it’s my turn, they roll me into a crowded room with two nurses, Dr. B, Barbara, and the anesthesiologist. There are machines on counters, thick printouts stacked high. I’m suspicious of messy places. The first time I was in this room, I worried. I hoped the chaotic feel of the space wasn’t an indicator of incompetence or lack of attention to how my care was handled.

When I’m the first patient of the day to be treated, everyone stands around waiting for one of the in-demand drug dealers from the anesthesiology team to show up. I’ve never had the same one twice, or I just don’t remember, which is a distinct possibility. My memory is awful right now. Since I’m one of the last in line today, the guy who’ll knock me out is already here.

Dr. B says “Hi,” and asks how I'm feeling, but seems more interested in playing with his precious machine and the leads that will be attached to my temples, my pulses, my heart. He flips through my file quickly, barely scanning the depression scale I just filled out. I have to fill one out every time.

I wonder if he uses that to gauge how many milliamps I get today. Less? More? Same?

While the docs are hooking me up to the electrodes, the drugs, and the monitors, Barbara gears up, to do her part. She goes through the same checklist of questions each time to assess my lucidity, my memory. “Where are you? What day is it? When’s your birthday? Why are you here?” I answer them, always surprised that I have trouble recalling the meds I normally take, but I never forget to remind them that they give me an extra 2mg of Ativan and a painkiller to stave off the terrible headache and jaw pain that awaits me.

The anesthesiologist is ready to open the flow into my vein, and he warns me that it will probably burn a lot going in, but not for too long. I know the drill. They put an oxygen mask over my mouth and nose and ask me to count backwards from 100 by sevens. I never make it past 86.

What the doctor doesn't know is that I love to feel that burning, crippling sensation in my hand. It’s so painful that it feels good. Comforting. Because I know that when I feel that burn, I’ll be gone in moments. It means that soon I won't feel anything. Soon, I can pretend that I die, if only for a few minutes.

There’s a part of me that hopes I’ll never wake up.

But before I disappear, I wait for it. I wait to hear her say the thing she always says.

Standing to my left, Barbara says, "hold my hand, girlfriend."

And I do.

1. I’m so grateful when readers decide to support my writing by becoming paid subscribers, and for the WHOLE month of June I’m running a Happy Pride month sale. 50% off my regular price for annual subscriptions.

2. If paid subscriptions aren’t your thing, but you still want to express your gratitude for my essays from time to time, a contribution is always appreciated.

3. AND, there’s another thing that you can do that doesn’t cost a thing. On the top or bottom of the story, you can click on the heart and “♥️” my essay, click on the speech bubble (💬) and leave a comment, and/or click on the little spinny arrow thingies (♻️) and restack the post (“restack” means “share” in Substackese). Those three actions will help me reach more readers!

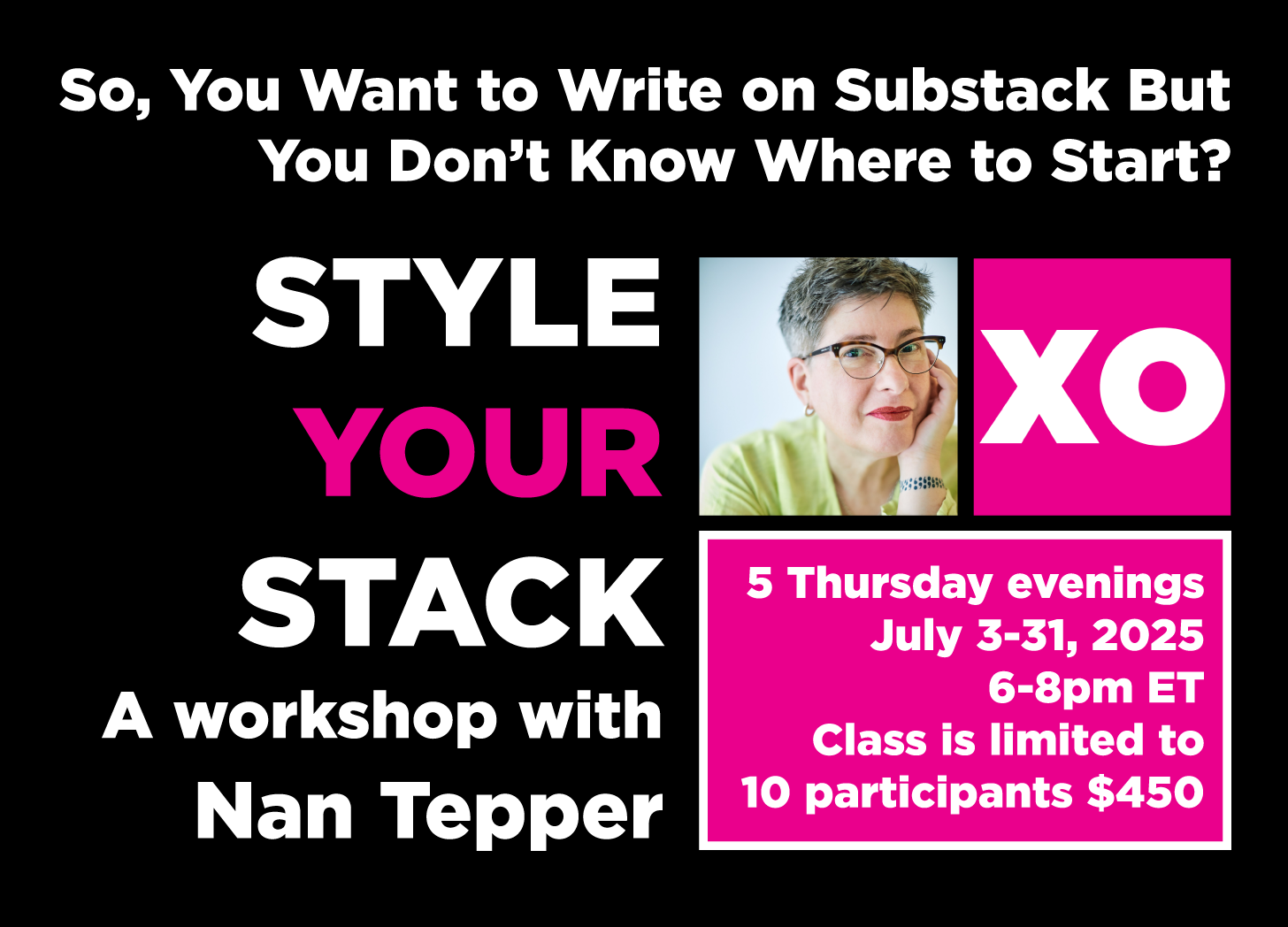

In July, I’ll be teaching my Substack 101 Workshop, again. It was a big hit in May! For any of you who are considering dipping your toe in the Substack pond, I can help get you started. For more info on the workshop, click the title below.

So, You Want to Write on Substack But You Don’t Know Where to Start?

You captured the power of one big heart in a dehumanizing place. And you opened up abput a stigmatizing experience. Here’s to you, Nan, and to the Barbaras of this world.

Such a beautiful piece of writing. I'm just jumping in, so I don't know if this is an ongoing story, but I knew exactly where you were and what was happening, without being told. I knew because you brought me right into the rooms and I welcomed Sal and Barbara on your behalf because I already knew they were your people, the real caregivers in the room. I have never had this experience, but you have expanded my understanding and compassion by sharing it with me. Thank you Nan.